Homes of the Century: 100 years of leisurely living rooms.

Tuesday, August 11, 2020

In this installment of Schlage’s Homes of the Century series, we look at the history of living rooms.

Small and separate to start

Industrial magnates of the 1920s – think Rockefeller – have always had huge homes. The rest of us, however, are a bit more modest. Particularly at the turn of the 20th century, homes were small and their closed floorplans may have made them feel even tighter. Closed-off rooms weren’t merely for design, though. Before wiring homes for electricity, families relied on gas lighting. A draft could quickly turn dangerous, so divided rooms were needed for safety.1

Electricity made its way into the average home in the 1920s, but it was still expensive. The tradeoff for electricity was building smaller homes with fewer rooms. The separate front parlor, common in Victorian-era homes, was eliminated and living rooms were born in its place.

That didn’t mean Americans were ready for an open-concept home yet, though. Looking at blueprints from the 1921 Sears, Roebuck & Co. catalog, from which prospective homeowners could purchase the plans to build their own house, we can see that each room was clearly defined. There was no mistaking in the Avalon floorplan, for example, that each space – living room, dining room, kitchen – was definitively designated for a specific purpose.

The relative luxuriousness of the Avalon should also be noted. Not only did the living room have space for a davenport and a piano – two features frequently called out in blueprints of the time – but it also had an indoor bathroom. The more modest Arcadia, on the catalog’s preceding page, had a smaller living room – no davenports here – and no dedicated lavatory.

Opening to new room combinations

A few decades later, new homes were still small by today’s standards, but we were toying with the idea of multi-functional spaces more regularly. By the 1950s, we see more living/dining rooms. One floorplan found in the Practical Homes catalog from 1953, advertised an “attractive contemporary design with its combination living and dining room (that) offers an interesting change to those who want a house planned for low cost livability. Truly individual, it has all the attributes of permanent worth.”

In other instances, the combination was a kitchen/dining area with separate living and family rooms.

During this transition from single- to multi-purpose, we also changed how we outfitted these spaces. The 1920s living room was advertised as a space for relaxation. In addition to the davenport – in the U.S., typically a couch that converted to a bed – and piano, there might have been built-in bookshelves, a library table and a fireplace.

With combination spaces, whether dining/kitchen or dining/living rooms, the focus shifted to convenience, extra space and improved airflow. We see all of these notes in the Practical Homes catalog. “Following the approved trend, the dining and kitchen areas are combined for efficiency as an aid to the busy housewife,” said one blueprint description. “The undivided living and dining portions increase the spaciousness of the house,” said another. And, “This home was carefully planned for livability. Cross-ventilation is had in the combination living room-dining room.”

Going lower for an elevated look

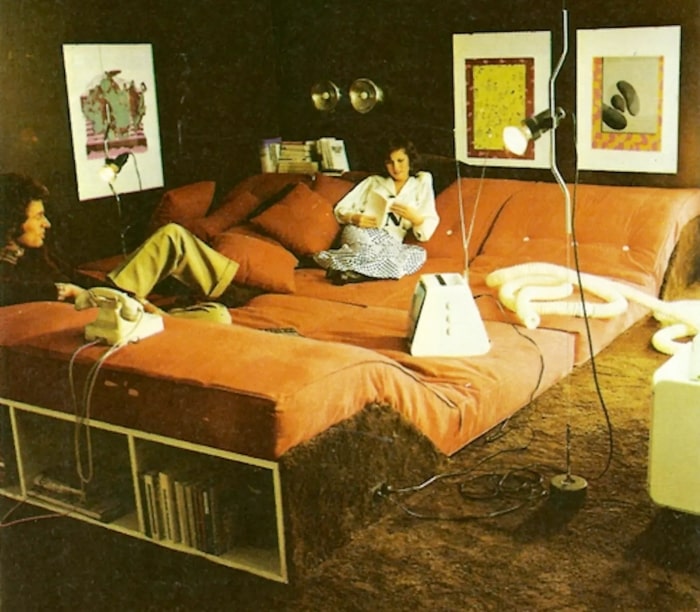

Housing trends come and go, and sunken living rooms are no exception. In the 1960s and 70s, they were the hot solution to open floorplans when you wanted well-defined rooms without sacrificing the spacious, airy feeling. The lower level also opened the door for conversation pits.

We understand better than ever now how relaxation, recreation and connection with others affect our quality of life. As we look to our surroundings to help us find balance and wellness, we may not need to look any farther than our living rooms, sunken or otherwise, to give us that boost we seek.

For more home history and to help Schlage celebrate its 100th anniversary, visit Schlage.com/100.

1 Kyvig, David E. Daily Life in the United States 1920-1940: How Americans lived through the 'Roaring Twenties' and the Great Depression. Ivan R. Dee, 2004.

2 “Leisure Home Focuses on Entertainment.” Architectural Designs, April 1987, p. 34.